By Sage Birchwater –

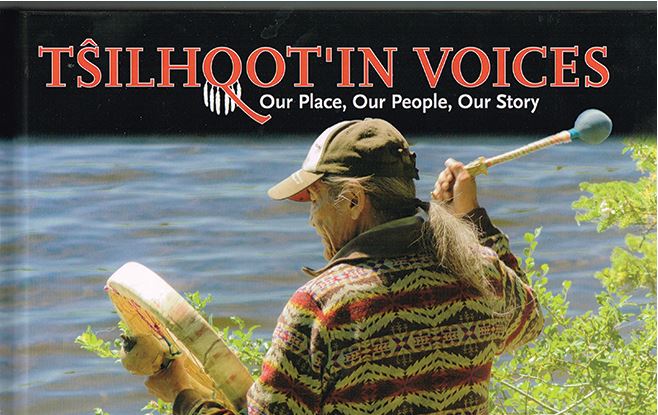

If a picture is worth a thousand words, then the recently released book Tsilhqot’in Voices: Our Place, Our People, Our Story is a veritable encyclopedia.

Published in late 2018 by the Tsilhqot’in National Government (TNG), the book’s 62 spectacular photographs and quotations from 18 Tsilhqot’in elders, leaders, and youth offer a fresh new look at the Tsilhqot’in people, their history, culture, and territory they have occupied for millennia.

The book creates a unique sense of place and offers a concise historical perspective. Of particular interest is the map of the region with Tsilhqot’in place names.

“For countless generations before the arrival of Europeans, our ancestors (the ?Esggidam) thrived as a powerful nation guided by the wisdom of our legends and the laws of our people,” the book begins.

Most of the text is a composite of statements made by Tsilhqot’in speakers at the federal Environmental Review Panel hearings of 2010 and 2013. Tsilhqot’in citizens spoke eloquently against a proposal by Taseko Mines Ltd to build a copper/gold mine at Teztan Biny (Fish Lake) in the caretaker area of XeniGwet’in and Yunesit’in.

Hearings were held in each of the six Tsilhqot’in communities of XeniGwet’in, TsiDeldel, Tl’etinqox, Yunesit’in, Tlesqox,and ?Esdilagh, as well as in Williams Lake.

The book allows the Tsilhqot’in People to tell their story in their own words. Tl’etinqox Chief and Tribal Chair Joe Alphonse says it provides good insight into the Tsilhqot’in nation.

“It’s important to capture the moment of where we’re at socially and culturally,” he says.“I’m excited the book came out the way that it has. I hope it’s well-appreciated by other people.”

Alphonse says in 10 or 20 years’ time the book will take on greater significance as a record of Tsilhqot’in identity.

The book opens with a dedication to Tsilhqot’in citizens, Elders, and ancestors whose testimonies at the decades-long Tsilhqot’in Supreme Court case and two Environmental Review Panel hearings were tantamount to the success of these efforts. Fittingly, the photograph shows a line of leaders facing Teztan Biny (Fish Lake) with the spectacular backdrop of Dasiqox Mountain reflecting in the water.

The next page is equally significant with a map of Tsilhqot’in territory with place names of rivers, lakes, mountains, and important sites written in the Tsilhqot’in language.

The book is about the unity of the Tsilhqot’in People. At the 2013 panel hearings Elder Angelina Stump stated that Tsilhqot’in territory extends from the little creeks feeding the Tsilhqox River system to its confluence with the ?Elhdaqox (Fraser River). “That whole area belongs to the Tsilhqot’in,” she says. “We are one.”

At the 2013 panel hearing in Williams Lake, former XeniGwet’in Chief Roger William quoted Michelle Myers: “This land is our lifestyle, and if we keep it healthy, then it will keep us healthy.”

Images throughout the book tell the story. Spectacular scenery, mountains, rushing water, placid lakes, and people engaged in the activities of survival off the land, fishing, hunting, preparing food, and enjoying fellowship together.

On March 26, 2018 the Canadian government held a special day of exoneration in Ottawa for the six Tsilhqot’in war chiefs who were wrongfully put to death by the colonial government in 1864 and 1865. All sides in the House of Commons spoke as one articulating the innocence of the Tsilhqot’in leaders, affirming they were justified in defending their land and people.

Then on November 2, 2018 Prime Minister Trudeau arrived in Nemiah Valley to deliver the speech of exoneration directly to the Tsilhqot’in people on Tsilhqot’in title lands. A photo in the book shows the Prime Minister shaking hands with Chief Joe Alphonse, surrounded by other chiefs and elders. The event was choreographed so that Justin Trudeau and Chief Alphonse arrived at the staging area on horseback, Trudeau riding a black horse and Alphonse’s mount was white.

Chief Alphonse explains the symbolism. After War Chief Lhatsassin had been hanged in Quesnel in 1864, his riderless black horse made it home to his family on its own. “It had to cross two major rivers,” says Alphonse. The black horse represented a dark period in our history. I told Justin he needed to get on the black horse as a sign of reconciliation and

new hope.”

Alphonse admits the Prime Minister has been subject to a lot of criticism lately. “But I admire the fact that he kept his promise and showed up,” he says.

Tsilhqot’in Voices is available for sale at both TNG offices in Williams Lake and at the Open Book, Station House Gallery, and other book store outlets.

Note: Several of the fallen warrior’s horses returned home to the Chilcotin after their owners were hanged in Quesnel. It is said the black stallion belonging to Chief Telad, swam across the Fraser River, and made his way back to Chezacut, which had been Telad’s home.

Sage is a freelance writer and lives in Williams Lake with his partner, Caterina. He has been enjoying the rich cultural life that is the Cariboo-Chilcotin Coast since 1973.