By Van Andruss –

Like so many others of my generation, half-asleep in a commercially-induced fog, the awakening of my social imagination took place in the 60s. There was a mixture of influences, political and economic, that might explain how the awakening happened, but that’s not my interest here. My purpose is to call for another such uprising to pull ourselves out of this current social morass.

It would not be the same sort of movement as before. We’re 50 years beyond the 60s and things have changed radically. Yet similarities will persist. If such a movement takes place, deserting conventional careers in favour of alternative ways of living, it will likely happen among young people, for the older generation is commonly sunk in long-standing habits and a demanding array of obligations.

I must believe that young people continue nowadays to search for the good life, a way of being that is comfortable, interesting, healthy, and, especially, of benefit to others and to the planet. Unburdened with debt and heavy commitments, many are in a position to do something different.

The alternative to convention that my friends and I sought in BC in the 70s through the 90s took the form of a back-to-the-land movement. We fled the urban centers to locate ourselves in a natural setting, hungry for the wild, and BC, bless her, was the perfect place to carry out our impulse. The back-to-the-land movement largely took the form of sharing acreage with others. These were pockets of co-operation known as communes. They differed widely as to their ideals and the boldness of their effort to integrate varied personalities. But the belief was widespread among us that we were going to make a difference to contemporary society. As idealists, we truly believed we were going to change the world, that our actions would provide a model for social transformation. Such was the atmosphere in which we laid our plans.

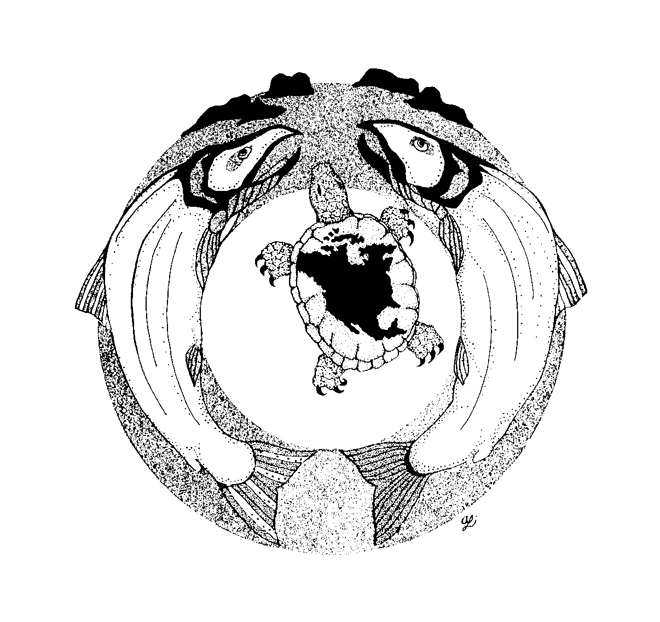

I would mention here that after the back-to-the land and communal period was well established, there emerged an interesting “alternative” in Northern California called bioregionalism. Some people may remember this movement. It was more adapted to a democratic mix of people than the shared-property, communal sort of arrangement, and for the first time in our hippy days we discovered a public movement with political overtones that we could join with enthusiasm. We had dropped out of the mainstream, but through this new idea we could find our way back into the wider world from which we had distanced ourselves. Our commune was so taken with the idea, we co-published a book on the topic: Home: A Bioregional Reader (still available from New Society Publishers).

Although bioregionalism has passed its heyday, its ideas are alive and dispersed in the contemporary social medium, as, for instance, permaculture, an all-species ethic, eco-feminism, strong support of Indigenous peoples, a belief in community, and settling into specific place, what we called, as non-natives, “re-inhabitation.”

These remain positive responses to the current business-dominated civilization.

What I wish to leave the reader with is the call for further exploration of alternative social relations. Let us not succumb to the corporate model aggrandizing the One Percent. If the communal movement and the bioregional ideals did not fully develop a conscious call for a new culture, they were at least headed in that direction. And it is precisely a new culture, a more integrated, more community-minded, settled, and joyous culture that we need at this historic moment.

Such an ideal would have to be experimental. There is no textbook to inform us how to organize a humanly satisfying shift in our cultural bearings. We can only reach this goal by trying out different ways of living, different lifestyles, feeling our way as we go to find what is fitting to the experimenters involved. The experiments I am proposing will not be like ours in an earlier generation. They will be diverse in their organization and character. The beginnings will be made by circles of friends who have seen through the futility of subjecting themselves to a standardized world. They will have realized there must be a better way. Once the social imagination is freed up from its market-centered enchantment, novel alternatives will spring up.

What I envision is small, local, integrated societies – with an emphasis on small – capable of a certain independence. I think of these units as watershed societies, similar to extended families, consisting of people who understand the necessity of caring for each other and the land. They may well come from city circumstances where they have met and have picked up on the idea of creating community. It will have become obvious to them that pooling their resources and their talents can open up new possibilities, new powers, which, as isolated individuals or couples, they could not even have imagined. Their dreams will likely take shape in a rural setting where it is possible to grow food and provide the necessary focus for making a new start. And most likely such experiments will emerge on the West Coast of this continent, just as they did before in the last century.

It seems we have heard all we need to of global concerns. The time has come to turn our attention to the health of our local places and our domestic arrangements.

After a long term of uprooting, let us set about re-constructing wholesome familiar worlds.

Let’s settle down, re-create community, and make ourselves at home again.

Van Andruss is editor of Lived Experience, an annual anthology of poetry, essays, and stories from BC and beyond. Van is a bioregionalist who lives a simple life in community in the Yalakom Valley, BC and can be reached at [email protected].