By Peter Shaughnessy –

By Peter Shaughnessy –

Conservation work in the West Chilcotin and Tatlayoko has protected significant areas of habitat for a wide array of species. It took years of work, lots of compromise, and countless volunteer hours to accomplish this. The initial goal was to slow the headlong rush to extract natural resources, particularly timber, thus giving time for long-term planning that included all other values. What follows is a summation of the work done over the past three decades.

There is a consensus among stakeholders in the Chilcotin that access to resources is critical to everyone but that this must not thereby destroy other values. In particular, those values that do not have a direct economic benefit require representation. The willingness of Chilcotin stakeholders with diverse perspectives to acknowledge this was the foundation of compromise that brought us to a common point.

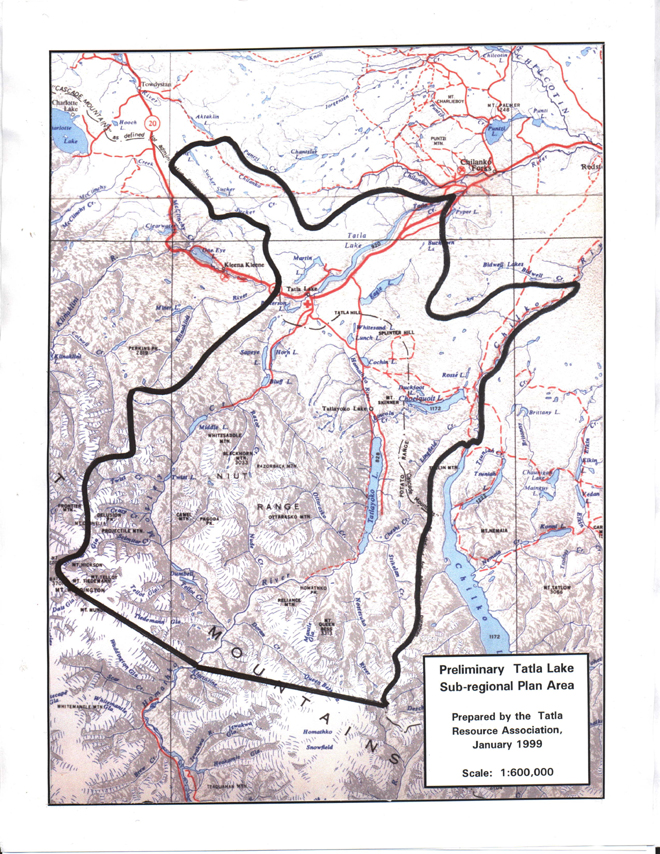

For the purposes of this article, the area considered is an 800,000-hectare subset of the 2.2 to 3.2 million hectares (depending on how it’s defined) of sparsely developed land called the Chilcotin Plateau. This subset was identified by the Tatla Resource Association as their Area of Interest and includes the communities of Kleena Kleene, West Branch, Tatlayoko, Eagle Lake, Tatla Lake, Puntzi, and Chilko River.

The Chilcotin is served by a single arterial road, Hwy 20, starting in Williams Lake and terminating at saltwater in Bella Coola. Along the way there are a few small communities (pop. ~3500 people) and mile after mile of wilderness. Situated on the Chilcotin’s south-central edge is its heart, the Tatlayoko Valley (pop. ~65).

The area has been occupied by First Nations for centuries. In fact, Tatlayoko is an anglicized version of TalhiqoxBiny, a First Nations word purported to reference the strong winds the lake is known for. There is a rough-edged and raw wilderness flavour here and the area remains much as it has been for many hundreds of years. The combination of wild spaces, few people, not too close to urban centers but not too far, and the appealing climate has attracted a unique mix of residents, including a high proportion of conservation-minded folks. People here are self-reliant and live ‘in the edge’ of wilderness rather than ‘on the edge’.

Much of our province is rich in natural values. So why is this area so important to conserve? There is a unique mix of species and habitats. Some of the more notable are the only nesting population of White pelicans in British Columbia, the second largest Sockeye run in BC, healthy populations of large predators and fisher, and the largest herd of woodland caribou in BC.

The area is also a confluence of seven biogeoclimatic zones and has tremendous vertical diversity. Scientists believe the Homathko and Klinaklini Rivers provide an important corridor between the coast and the interior, particularly for grizzlies. They surmise that not only are these corridors important for movement of species, but also for their continued survival in the face of climate change.

Despite being only 180 (straight line) miles from Vancouver, the natural systems that have sustained the area for millennia are still essentially whole. This makes the area a natural candidate for pre-emptive conservation. In other words, conserve functioning ecosystems before they are compromised or destroyed. Conserve enough space with enough connectivity to allow species to live and adapt as required and also to protect the natural values that bring people here.

There are threats to the natural systems here including mining, increased human settlement, invasive plants, climate change, and intensive road building/access. But the focus of conservation effort has been, and is necessarily still, industrial timber harvest impacts.

The area has attracted substantial conservation interest from government, private conservation organizations, First Nations, and residents, including buy-in from industry. A mosaic of conservation areas has been created since significant work began in the early 1990s. Progress has been iterative and cumulative, each piece contributing to the whole.

Beginning in 1990, Fritz Mueller and a few other residents of Tatlayoko submitted the Niut Wilderness Proposal for consideration by government. They proposed that the Niut Range be officially protected as a wilderness area. Their efforts were not successful. Nevertheless, Mueller’s work began the conversation about the threats to Chilcotin wilderness values and the importance of conserving them.

In 1994, after five years of negotiations between the province, First Nations, and other stakeholders, T’sylos Park was established. It protected 233,000 hectares of high quality wilderness.

From 1992 to 1996 the provincial government held the Commission on Resources and the Environment (CORE). This plan mapped special management zones through consensus negotiations with stakeholders. The result was land use designations that provided guidance to subsequent planning processes. Lack of political will resulted in inaction, and land use objectives outside of protected areas were not made legal. Fortunately, the plan did legislate the Homathko Protected Area. It contained 17,500 hectares of diverse landscape, incorporating low elevation coastal rainforests, wetlands, and the western shore of Tatlayoko Lake.

In the mid 1990s, an Integrated Resource Management Plan was undertaken for West Branch. The focus was mitigation of timber harvest impacts on non-timber values. After six years the product was rolled into a subsequent planning process. According to West Branch resident Deborah Kannegeiser, “Our work essentially held off timber harvest until such time that government could catch up with their planning process”.

In the late 1990s, stakeholders at Anahim Lake met for five years to negotiate the Anahim Round Table, which was approved by government in 2001. It covered an area from the boundary of Tweedsmuir Park to Kleena Kleene. Again, the focus was primarily industrial timber harvesting, where to do it, and how to protect non-timber values.

The province’s Cariboo-Chilcotin Land Use Plan was designed to provide a strategic framework for land use. For detailed operational planning, the area was to be broken into manageable subunits called Sub Regional Management Plans (SRMP). SRMPs were completed for 100 Mile House and Quesnel in 1996 with the Chilcotin Plan being reserved for last.

In 1999, the Tatla Resource Association (TRA) was formed by residents of the Tatlayoko area in response to large scale timber harvesting proposals. After identifying their area of interest, the group successfully lobbied the government for a logging moratorium until the plan could be completed. Over the next five years the Tatla Community Plan was crafted. It brought 85 diverse individuals together in consensus on where logging should and should not occur and identified areas of special interest to the community. The guiding principle of the TRA was sustainable resource extraction that respected all values.

In 2000, the Nature Conservancy of Canada (NCC) recognized the conservation significance of Tatlayoko and the West Chilcotin. Their work here began with the purchase of Tatlayoko Lake Ranch. Fifteen years later they have conserved over 4,000 acres of private land in Tatlayoko and along the upper Klinaklini River. During those 15 years, NCC conducted and sponsored a significant body of scientific research in Tatlayoko. NCC is no longer a proponent of research, although they encourage third-party research on their properties. Today, their role is simply to steward their existing lands.

In 2003, the West Chilcotin Demonstration Project brought together a partnership between the TRA, Alexis Creek First Nation (ACFN), Tsi Del Del Enterprises, the West Chilcotin Tourism Association, and the province. This group looked for a way to meet government timber targets while protecting non-timber values. The group overlaid the Tatla Community Plan with a similar plan from ACFN to identify areas of common interest. The amazing result was a consensus plan provided to government for inclusion in the Chilcotin SRMP (see map below).

The relationships and the trust established between ACFN and the TRA was formalized in the TatlaTsi Del Del Agreement signed by all in 2005 and blessed by the Minister of Forests. This agreement eventually led to creation of the Eniyud Community Forest (see map above).

The Chilcotin SRMP covered 2.2 million hectares and among other things identified no harvest zones and special management zones. Special management zones allowed 70 per cent of the land base for timber harvest and 30 per cent for non-timber values and uses. With the TatlaTsi Del Del Agreement as a guide, the various stakeholders negotiated to lump the 30 per cent into high value conservation areas. The result is that the plateau is available for industrial timber harvest, an intermediate zone closer to the mountains was designated partial harvest, and the remainder was designated no harvest.

The Chilcotin Ark is an initiative conceived by Ric Careless of BC Spaces for Nature. The Ark is a sweep of land that follows the inside of the Coast Range from Ootsa Lake to the Fraser River just north of Lillooet. It encompasses a broad spectrum of ecosystems including 10 of the 16 biogeoclimatic zones that exist in BC. Work on this initiative continues today.

Eniyud Community Forest is a 50/50 incorporated partnership between the TRA and ACFN. While it is clearly a timber harvesting licensee, it has a basis in conservation and is guided by the TatlaTsi Del Del Agreement. After six years of operation the company is well established and has a bright future. Timber harvest decisions are made jointly and profits are retained within both communities. Sustainable harvest and local employment are major objectives.

What is the current state of conservation in the West Chilcotin? Plans provide essential guidance for managers but they have their limitations. Without periodic reviews and updates they soon become either irrelevant or forgotten. For much of the planning work above it’s time for revision and renewal.

The XeniGwet’in Title Case has been a game changer for the Chilcotin and British Columbia. How the band decides to manage its Title Lands over the next few decades will set the tone of conservation for a big piece of the Chilcotin.

Some of the objectives of the Chilcotin SRMP are legislated while others are considered advice only and as such are open to change or alternate interpretation.

Climate change and carbon sequestration are the new buzz words. Climate change is a reality and its effects are clearly being felt. It remains to be seen whether carbon sequestration will play a role for conservation in the Chilcotin but it is being looked at.

Recently, a group of young and motivated Tatlayoko residents have formed a new group. The Chilcotin Ark Society is a non-profit whose mandate is to support traditional and scientific research on ecology and climate change, experiential nature-based learning and personal development, and sustainable community development in the Chilcotin.

I am optimistic about the future of conservation here but I know vigilance is required. I hope people will look back a century from now to see the results of our efforts. Fritz Mueller put it to me this way, “A lot of good conservation work has been done but a tremendous amount remains. Many of our gains are still vulnerable.

Many conservation proponents are getting older and the younger generation must become involved”.

Peter Shaughnessy is a resident of Tatlayoko since 1988, artist, construction contractor, director of the TRA, director of the Eniyud Community Forest, and former employee of Nature Conservancy of Canada.