By Margaret-Anne Enders –

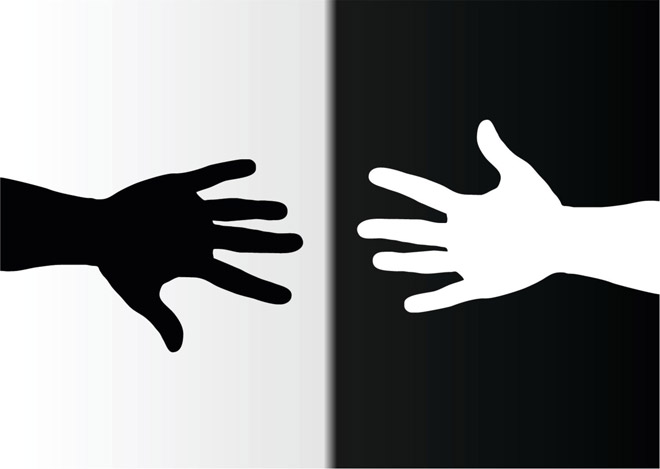

Apparently there is a name for it. A phrase that encompasses the gut-churning, oxygen-sucking, confidence-shaking, grief-provoking physical and emotional onslaught that greets those who step onto the path of working for racial justice and equality, who dare choose to stand beside and actively walk with those who are marginalized in our society. It is so real a phenomena that it has its own name. It’s called “sitting in the fire”.

I am well-acquainted with the virtue of being able to sit in discomfort, to observe the thoughts and feelings that arise, to feel the sensations in the body, to regard them without judgment, and to just be present as the thoughts, feelings, and sensations change and often dissipate. I try and observe this as part of a regular practice and sometimes even feel like I do pretty well with it. Until the next time I get overcome and do whatever I can to quickly get rid of that uncomfortable feeling. But let’s just say I know how to do it, even though I sometimes am not able to. But this – sitting in the fire – that takes the practice to a whole new level.

What is it that makes this practice so different? I think it is because doing work aimed at addressing inequalities forces contact with those inequalities on not just a personal level, with looking at my own thoughts, feelings, and reactions, but it also necessitates looking closely and critically at how I move in the world, my relationships with others, and how my actions affect those relationships. Additionally, it requires a level of observation and analysis about the social structures amidst which we live and then using that structural information to see how my own interactions mimic what is happening on a structural level. It is dizzying and complicated and sometimes feels just too hard.

It is hard. It’s hard on an emotional level. The more my eyes are opened to injustice, the more I can see it everywhere. On the police show Blue Bloods, when an officer kills an unarmed woman and there is no analysis of race, but an immediate defense of the white officer. In the reporting of events in Edmonton and Las Vegas, how the one man who acted alone, but had brown skin and Arabic name is deemed a terrorist because he’s Muslim, but the other man who also acted alone, yet killed and injured so many more is not identified by colour, race, ethnicity, or religion, but is said to be a grandfather, a detail whose insertion automatically elicits a certain degree of empathy. When a Chilcotin chief calls for a moratorium on hunting except for indigenous people in this fire-affected, devastated area, and the Facebook comments are so hateful and racist, it makes my stomach go sour. There is so much hatred, so much injustice. It is hard to keep noticing, to keep witnessing, and even harder to see the beauty and joy that still is in this world. This fire is hot.

It is hard on a relational level, this work of standing with others. Those of us who, because of race, gender, socio-economic status, have more power and who want to use this power to help others and level the playing field, we can be hard to tolerate. We make a lot of mistakes and have a hard time acknowledging them. We can be self-righteous and quick to point fingers. We tend to expect gratitude, even when what we have given might not be what is needed. We are often slow learners. We can get stuck in our own stories and forget to listen to and indeed privilege those stories of the people we have pledged to stand with. And we often want things to take the easiest road possible. We want marginalized people to agree, to speak with one voice, to have just one opinion about how to fix these messes that we folks with power have often created. But of course, that desire for one voice in itself diminishes the power and voices of those we want to stand with. So we must stay grounded somehow in the midst of many opinions, always trying to be respectful, but sometimes getting stuck not knowing how to act, or acting in a way that is unacceptable to some of our partners. We have to stand strong still, to bear the anger and the pain of those who yet again feel diminished. This fire is hot.

On a structural level, change is frustratingly slow. There is a lot of push-back against those who want to change structures. There is resistance and fear, and people who have more power in these structures often don’t feel like they do have much power and they fear the changes, fear losing hold of what little they feel they have. All the stops come out in misinformation, accusations, and aggression. This fire is hot.

As a part of the dominant white class, it would be all too easy to step back into a more comfortable space. But that in itself is a sure sign of privilege. Despite the heat, I must keep travelling the path. Even though I do and will make countless mistakes, I seek the courage to continue. I want a world where everyone feels safe and valued and where we all celebrate the richness that diversity brings. One of my guides on this path, Camille Dumond, the same guide who taught me about sitting in the fire urges, “In the midst of the fire, hold on. Stick with it: this is warrior training. Remember that your intentions mean something, your vision for the world is important.” I take a deep breath, sit in the fire, feel its burn, and resolve once again to take my place on the road to justice in this world.

In her work with the multicultural program at Cariboo Mental Health Association, as well as in her life as a parent, partner, faithful seeker, left-leaning Christian, paddler, and gardener, Margaret-Anne Enders is thrilled to catch glimpses of the Divine in both the ordinary and the extraordinary. To find out more about the Women’s Spirituality Circle, call (250) 305-4426 or visit www.womenspiritualitycircle.wordpress.com or on Facebook at Women’s Spirituality Circle in Williams Lake.